Free online learning for adults: click here

Free online learning for adults: click here

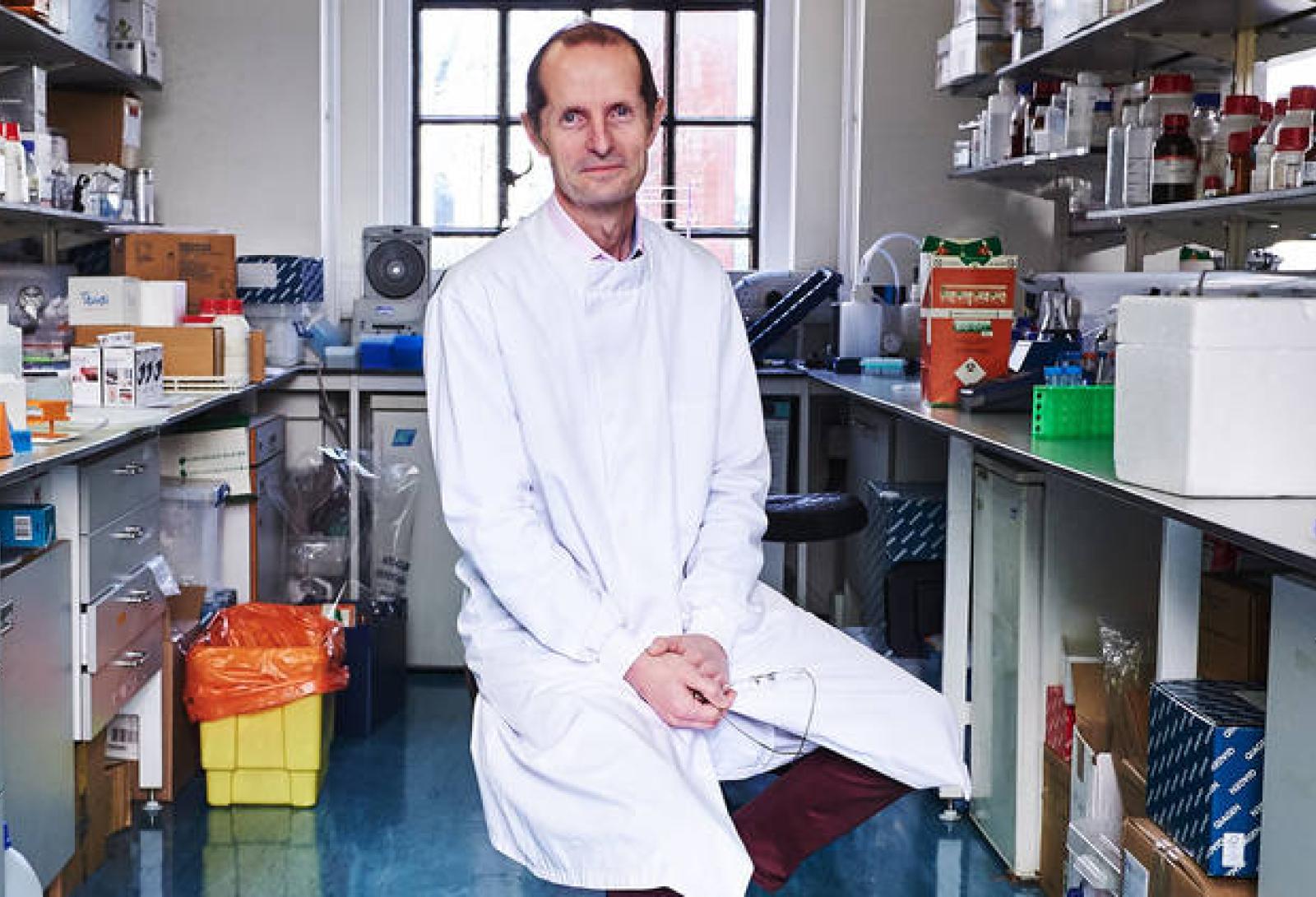

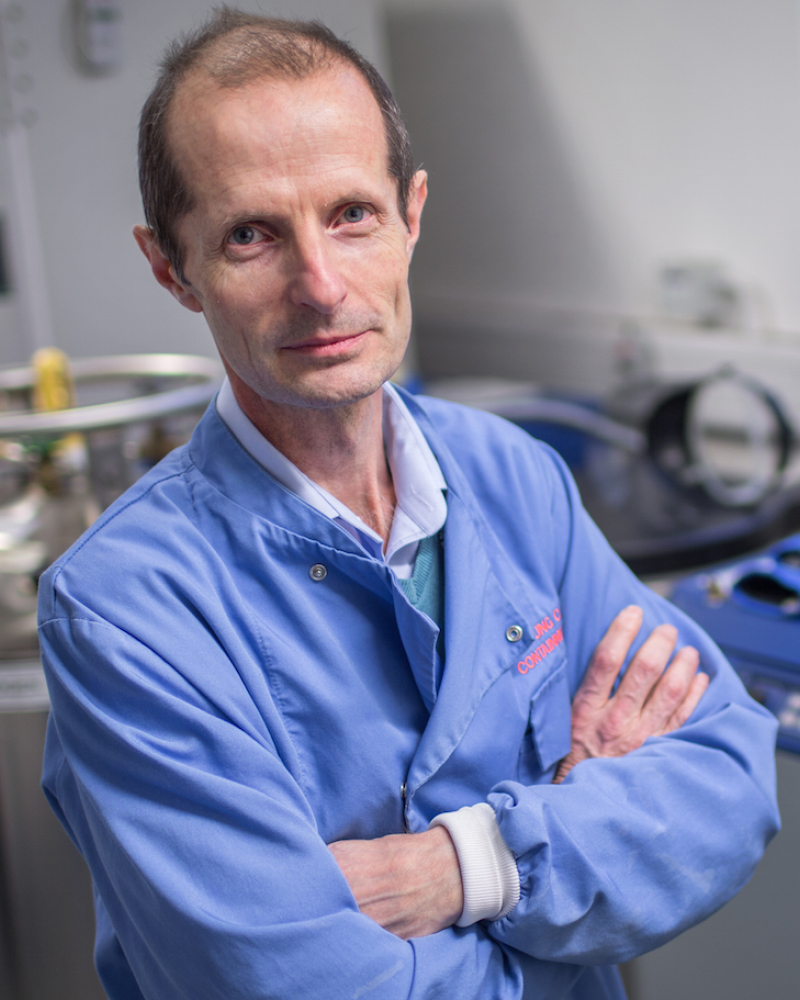

An internationally-renowned scientist who pioneered a new generation of medical technology has described studying at Nescot as a ‘turning point’ in his life.

Professor Robin Shattock led work at Imperial College London to develop a Covid-19 vaccine in 2020, and his team’s findings could be extended beyond vaccines to other types of medicine.

He told Nescot that science is ‘on the cusp of something revolutionary’ and spoke of his pride at being involved in what he said was the most exciting part of his career so far.

“This is the next generation of technology,” he said. “It works for other aspects of medicines where we want to encode a protein, so the potential is enormous.

Professor Shattock studied at Nescot in his twenties, starting with an HND in Microbiology and progressing to specialise in Immunology. He finished his degree with a First.

“Nescot was great for me because it allowed me to forge an alternative career path,” Professor Shattock said. “I was able to study later in life, and that was definitely a turning point for me.

“I feel sure that if I’d taken the conventional route to university I would have come away with a Third, and I probably wouldn’t even be working in science.”

Professor Shattock has developed a way of sending highly-specific instructions to the immune system using genetic code called self-amplifying RNA, or saRNA.

This means only tiny doses of vaccine are needed to create immunity, which means vaccines could be cheaper and faster to produce, theoretically reducing vaccine inequality across the world.

Professor Shattock has set up a company called VaxEquity, which last year signed a deal with AstraZeneca worth £195million in milestones to work on up to 26 new drugs.

Professor Shattock has been involved vaccine research for more than three decades, leading and coordinating the pan-European effort to develop an HIV vaccine as well as working on Ebola, rabies, influenza and chlamydia.

In early 2019 he gave a talk at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, on new vaccine technology and how it could be used in a pandemic.

“Very few people turned up,” he said. “Scientists had been predicting a new pandemic for a decade already, and there was a sense that not many people believed it would actually happen.”

Later the same year he was working on saRNA research when he and his team started hearing about a new type of Coronavirus circulating in China.

“I remember saying to two post-doctoral students, ‘Shall we start working on a vaccine?’, and one of them said, ‘No, this will be a flash in the pan’,” he recalled.

“The genetic sequence of what went on to be named Covid-19 was published on January 10, and we had a vaccine candidate within 14 days.”

Professor Shattock’s research was given £50million by the UK government, which at that point was nervous about being able to access vaccines and wanted to be sure that there was a British candidate.

“It was intense,” he said. “We had to work quickly, and we were under a lot of pressure. It was unknown what would happen internationally, and I wanted to be sure we had a strong candidate.”

The Imperial candidate did not go on to be used as a vaccine, but both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines use RNA technology, which Professor Shattock described as ‘really exciting’.

“Our team was definitely challenged by not having a large pharmaceutical company behind us at that time,” he said.

“It’s really exciting that the RNA technology has been proven on such a large scale. No one had had much success before this – Moderna and Pfizer had both been working on the technology for years.”

Professor Shattock is hopeful that RNA or saRNA can be used to develop an HIV vaccine, which he describes as ‘one of the biggest scientific challenges of a generation’.

He said: “We’ve got a long way to go, but yes I am very hopeful that it will happen within my lifetime.”

Professor Shattock said he is hoping that one unexpected positive to come from the pandemic will be an increase in people studying science.

“Hopefully the vaccine development process has helped people to see that science is relevant, current, exciting, and can change people’s lives,” he said.

“Careers are made by opportunities, so seize them where you can. Never feel that because you haven’t gone the traditional way that your achievements or progress is any lesser than anyone else’s.”

Professor Shattock enjoyed acting and music at school, and dreamt of being a rock star. His A-Levels in Biology, Physics and Chemistry went badly, he said, and afterwards he took a series of odd jobs.

Eventually he joined what was then Guildford Public Health Laboratory as a research assistant, feeling sure that he was the only candidate for the job.

“I remember saying to my wife, ‘I can’t stay here. The work is so difficult, and everyone is so serious’,” Professor Shattock recalled. “Eventually something clicked, and it all started making sense.”

From there he studied at Nescot, initially doing an HND in Microbiology on day release and then specialising in Immunology for his degree.

“Nescot was a fun place to be,” he said. “Immunology in particular was extremely well taught, the teachers were responsive, and the environment was really stimulating.

“I left with a solid grasp of different aspects of immunology, and also a fundamental understanding of research that informed my career from there.”

After studying at Nescot, Professor Shattock took a job at St George’s Hospital Medical School. He was working there when the first UK cases of HIV were recognised, and he helped to set up a specialist research laboratory.

He worked there for 21 years, working towards a PhD and then becoming a Professor, before moving to Imperial College London in 2010.

Useful links